Consensus Algorithms

Byzantine Generals’ Problem

As we saw in the Byzantine Generals’ Problem, this challenge has been around for a while - achieving consensus in a distributed system with suboptimal communication between participants who do not necessarily trust each other isn’t new.

Proof of Work

Bitcoin figured out how to use the Proof of Work algorithm to solve this issue.

The main innovation that Satoshi Nakamoto introduced in Bitcoin’s white paper is using Proof of Work (PoW) to achieve consensus without a central authority and solve the double-spend problem.

How Does It Work?

PoW involves miner nodes, or miners, to solve a math puzzle that requires a lot of computation power. Whichever miner is able to solve the puzzle the fastest is able to add a block of transactions to the blockchain, and in return, they are paid the transaction fees from all the transactions included in the block as well as paid by the network with bitcoins that were newly created upon the “mining” of the block.

Potential Issues

2 Commonly discussed issues with Proof of Work are:

Extremely High-Energy Consumption

A Monopoly of Miners which Leads to a Concern for System Centralizations

Proof of Stake

In the Proof-of-Stake Consensus Protocol, there are no more miners; instead, there are Validators. These validators, or stakeholders, determine which block makes it onto the blockchain. In order to validate transactions and create blocks, validators put up their own coins as “stake”. Think of it as placing a bet - if they validate a fraudulent transaction, they lose their holdings as well as their rights to participate as a validator in the future. In theory, this check incentivizes the system to validate only truthful transactions.

Potential Issues

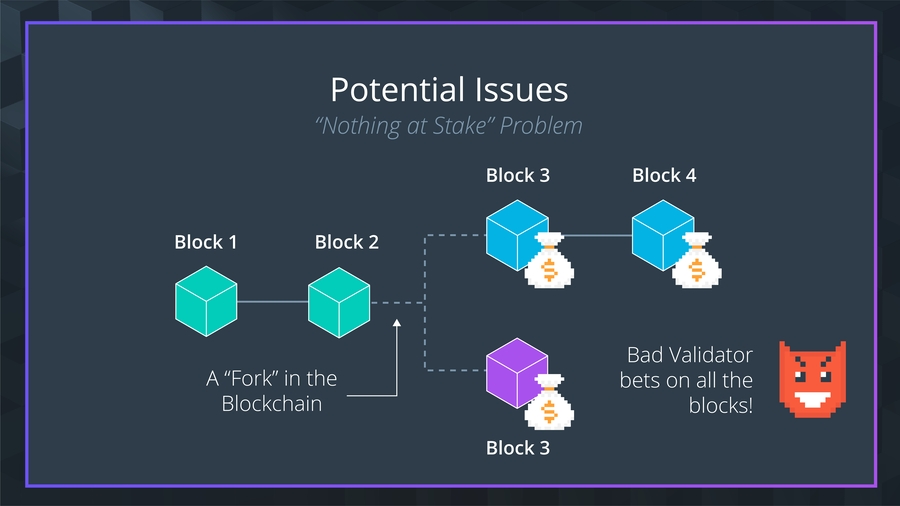

We discussed the “Nothing At Stake” problem in which a bad acting Validator places bets on multiple forks so they theoretically always win out in the end.

Proposed Solutions

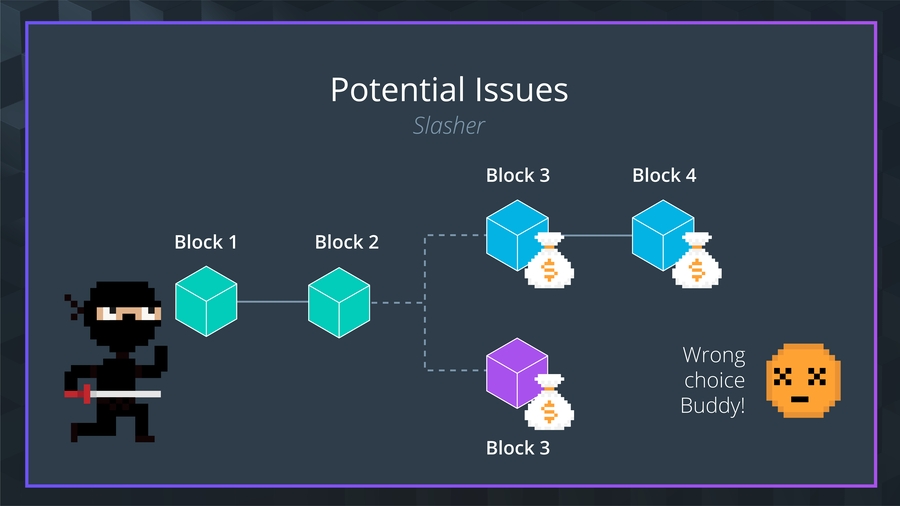

Slasher Strategy which entails penalizing validators if they simultaneously create blocks on multiple chains.

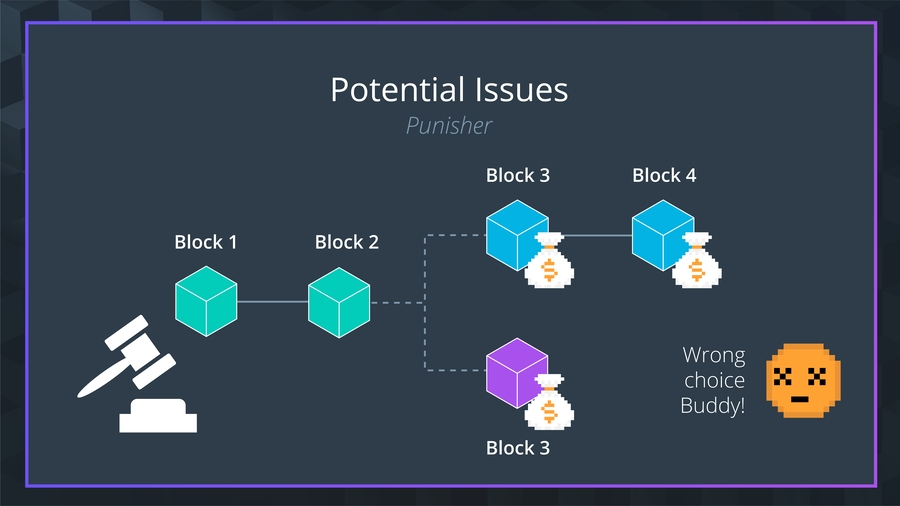

Additionally there’s the Punisher Strategy which simply punishes validators for creating blocks on the wrong chain. In this method, Validators will be motivated to be selective and conscious about the blockchain in which they put their stake.

Who’s Using It?

Ethereum, DASH, and LISK are big proponents

Ethereum’s Proof of Stake FAQs

Randomized block selection

Coin age-based selection

Alternative Proof of Stake Methods

Transparent Forging

Delegated Proof of Stake

Delegated Byzantine Fault Tolerance (dBFT)

dBFT uses a system similar to a democracy where Ordinary Nodes the system vote on representative Delegate Nodes to decide which blocks should be added to the blockchain. When it’s time to add a block, a Speaker is randomly assigned from the group of Delegates to create a new block and propose the new block. 66.66% of delegates need to approve on the block for it to pass.

Potential Issues

Two issues we explored were the case of the Dishonest Speaker and the Dishonest Delegate.

Dishonest Speaker

There is always a chance the Speaker, who is randomly selected from the Delegates, could be dishonest or malfunction. In this situation, the network needs to rely on honest delegates to vote the proposed block down so it doesn’t reach 66% approval. It is up to users of protocol who vote on Delegates, to find out which delegates are not trustworthy and vote on other delegates that are truthful.

Dishonest Delegate

In this case, the chosen Speaker is honest but there are Dishonest Delegates in the system meaning even if they receive a proposal for new block that is faulty, they can say it is valid. If it is a minority of delegates that are dishonest, the block will not make it and new speaker is elected.

Who’s Using It?

NEO is a big advocator of this protocol.

Proof Of Activity

Proof Of Burn

Last updated